May 2020 2

No woman’s land – my mother’s homeland

A short personal account of Yugoslavia and Macedonia from 1920 to 2020

It was 1984 and I was a seven-year-old boy with long messy “Beatles-like” hair, as my doctor father used to tease, and a motherless “son-of-a-gypsy-woman” as my grandfather, a no-nonsense WWII veteran, used to say. Of course my hair was messy; I was being raised by two egomaniac father figures, neither of which told me to comb my hair or dress properly оr all the other things that a mother would normally say. My parents were separated by then, my mother, a descendant of bourgeois “traitors” and my father, a son of a proud socialist partisan warrior. I was living in the Marxist paradise and didn’t even know what my mom looked like, she was like a ghost figure, guarding me from a distance of a thousand miles, whispering in my ear not to worry, to leave my toxic home environment as much as I could and go outside to play with my friends. The street was a place of zen-like calm and eternal happiness. Indeed, it was a magical year – the 1984 Winter Olympics were being held in my city of Sarajevo, now just a collection of old shelled and bullet-riddled Austro-Hungarian buildings.

As I search through my memories like the pieces of a puzzle, I think to myself, “Damn, it could just as well have been Nineteen Eighty-Four!” People informed on others to the party, even their friends or relatives, who then often lost their jobs or, as my paternal grandfather, were taken to prison, although he was a socialist. In the meantime, my socialist country fell apart. We endured a hellish, pointless war. I lost all my childhood friends. But I gained a new transition-to-a-capitalist homeland. And, yes, a mother too. But let’s be fair. Living in Yugoslavia under socialism in 1984 wasn’t so bad. Later, some even called it “Coca-Cola socialism”. It was true that we had all the benefits of capitalism, even Coca Cola, although we preferred the domestic Cockta, which, to be honest, didn’t taste as good as the sweet dark American drink it aimed to replicate.

Throughout history, but also in any one particular moment of the Yugoslav past, there were many realities. In one of those realities, my mom was born in 1950. She was the granddaughter of an industrialist, who came from Czechoslovakia to Skopje in the 1920s with dreams of building his little capitalist kingdom. And he succeeded. Since then, Skopje has been part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918-1929), the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929-1941), the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (1945-1963), the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1963-1991), the Republic of Macedonia (1992-2019) and the Republic of North Macedonia (2019). It’s mind-boggling, I know. In 1938 my great-grandfather, the Czech capitalist, built a factory called “Kumanovo” on the outskirts of Skopje, that had an automated flour mill, by my mother’s account the first of its kind in the Balkans. He also bought a lot of land, built several houses, and gave each of his daughters a house as a gift. Little did he and other wealthy people know that the war and, later on, socialism was coming.

Korda Family

My maternal grandmother, Nada Korda, was a large and strong woman, but only by her looks. In all of the pictures I have seen of her, she is gazing in the distance because she was burdened by a weak heart. Unlike her sisters, she didn’t want any material possessions. She had one wish only – to study art. Her father couldn’t say no to her and paid her tuition and living costs. Since there was no Faculty of Art in Skopje, she went to study in Belgrade, Serbia in 1938. When she finished her studies in 1942, she came back to Skopje. And like everyone else, she survived by tenacity and sheer will to live. In 1944 she married a capitalist, a wealthy young man who rode motorbikes, greased his hair, and smoked expensive cigarettes.

Image: Nada Korda (second on the left) with her relatives and one of her paintings above, Skopje, 1944

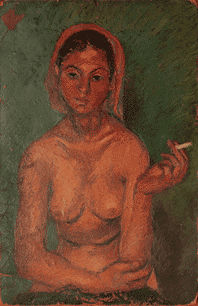

Image: “Gypsy Woman,” a painting by Nada Korda (1941)

Yugoslavia under the socialist regime was a wealthy country. There was no famine like in the USSR, and people were happy. Well, most of them, anyway. My paternal grandfather was imprisoned for five years in “Goli Otok” (literally “Naked Island” since there were only rocks and no vegetation). It was a hell on earth for political prisoners and he sure wasn’t happy. He was, however, a socialist and a WWII partisan veteran with thirteen bullet holes to prove it. But that’s nothing compared to the “traitor capitalist bastards” of my maternal grandparents. All the factories and houses they built were taken away from them by the legal processes of colonization, nationalization, and expropriation. That was the reality of socialism, not only for the city folk but for affluent landholders with a lot of livestock. The official story was that the socialist state took all of their possessions for the wellbeing of the people of Yugoslavia. But the reality was that all the private belongings that the state commandeered went into wealthy private hands of the communist leaders, which made the people poor. Like one of my mom’s grandparents’ houses, that was given to a general who, simply, passing down the street, saw the house and liked it! The family was given one night to move out.

In those circumstances, all of my family from my grandma’s side left Yugoslavia and went back to Czechoslovakia. All but my grandma. She stayed in Skopje with her husband and they lived a happy life… Of course, there are no happy endings in real life, but hey, there’s no fun and joy in life without difficulties! Her dream of becoming a professional artist was crushed by the war, the socialist nationalization of wealth, her illness, and her family leaving her. But she had a husband and, more than anything, she wanted to be a mother. The doctors advised her against having a child since it would be too great a strain on her weak heart, but to no avail – it didn’t matter to her. So, in 1950, my mom was born. There are not many pictures of my grandma from that period, but in those that I mentioned before, she always seems distant and looking into the future, as if she could sense that she wouldn’t be around for very long to see her child grow up. When my mom was nine years old, my grandma died. She left behind a husband without the love of his life, a house full of books that she read while confined to her bed, and many unfinished paintings.

Sima Family

And what about my grandfather? Well, he was crushed, of course, but this wasn’t the first tragedy of his life. His father was a Vlach (Aromanian), a people believed to have introduced urban culture to the Balkans. By the end of the Ottoman Empire, my great-grandfather was mayor of Kochani in Macedonia, a city famous for its rice production. In the 1920s he came to Skopje, already a wealthy man. He bought a house in the famous Skopje neighbourhood of “Pajko Maalo”, and opened a fabric store called “Simic”. His original surname was a Vlach “Sima”, but in the times of the Yugoslav Kingdom it was changed to “Simic”. Later, under fascist Bulgaria, it became “Simov,” in Macedonia “Simoski,” and finally back to Sima. That’s one of the wonders of the Balkans, changing your identity is quite a regular thing.

Image: Jika Sima, 1935

He and his wife had five children, two boys and three girls. The two boys went to university and graduated in economics, one in Paris and one in Skopje. After the death of their father, they ran the family business. The older one married a Bosnian woman and they moved with their two young children to Bosnia at the beginning of WWII. On the day of their arrival, the father and the little daughter, called Biljana, were killed in a Fascist ambush and died on the bus. The mother and the son survived and came back to Skopje. The grieving wealthy family gave the house in “Pajko Maalo” to the wife of their brother, and my grandfather called his first and only child – my mother – Biljana, in memory of the young seven-year-old daughter of his older brother.

Image: The girl that was killed in WWII (1940) and my mom who was named after her (1958)

As Socialism knocked on the doors of my family’s fortune, the “Simic” fabric store and all the possessions they had were taken. My mom lived with her family in rented flats and houses. But my grandfather, Jika Sima, didn’t give up. He opened a sporting goods store in Skopje called “Sport,” and then a furniture store called “Jugoexport”. He was part of the administration of the country’s best soccer club, “Vardar”, and was active in promoting winter sports, founding the “Mountaineering Union of Macedonia”. He was a tough capitalist nut to crack, but when my grandma died in 1959, he was devastated. Like all single fathers, he tried to fill the void of the maternal figure in the life of his daughter with strict rules, and he ruled his kingdom with a firm hand. Well, as you can imagine, that didn’t sit well with my mom. She was sent to live with her aunts in a village and had a seemingly pleasant rural experience filled with natural wonders before moving back to Skopje several years later.

My mother in socialist Yugoslavia

She was 13 years old when the new Socialist Republic of Macedonia, as a part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, lived through a catastrophe. Skopje was destroyed by an earthquake. Most of the buildings were destroyed. All the citizens of Skopje were given temporary living barracks. As the situation settled, my grandfather donated his barracks back to the state. He bought a house from his wife’s sister, where my mom still lives today. He was maybe the one and only person I know who gave back his barracks, since all the other citizens of Skopje built houses on top of their barracks, and later apartment buildings. And that’s how the city of Skopje came to be after the earthquake. It seems to me that my family has always valued hard work, sincerity, and effort. A lot was taken from them, but they never took anything that didn’t belong to them. My mom was raised by that principle, one I also believe in. Skopje was rebuilt with international aid from the East and West, and this brought to life some of the interesting brutalist architecture that Skopje was famous for in the 1960s and later on. In those times our socialist youth wasn’t any different from the youth of the capitalist countries. We also listened to British and American rock music and shook our hips to the sounds of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

The new decade was on the rise and my mom was 20 years old. Finally, let off the hook by her strict father, she enjoyed her time with her friends in Makarska, a city on the Yugoslav Adriatic Sea. It was then and there, at a party with the sound of Purple Haze by Jimi Hendrix in the background, that she met the man that would become my father. She left Skopje, and her father relocated all her belongings to Sarajevo. One year later she gave birth to her first love child, my sister. Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the 1970s was a different city from Skopje. It was a real mixture of Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman influences, and a mixture of nationalities and religions as well. In socialism, everyone was equal regardless of their beliefs. And they really were – under Marshal “Tito” the people used to speak his name as if he was the one and sole deity. “Brotherhood and unity” was the slogan of the Yugoslav nation and all the people lived by it, especially in Bosnia. The Bosnian people had a real sense of humour too, and in those circumstances, my sister was born and six years later, I came along. It was the great old seventies, hard rock, sideburns, modern homes, electrical appliances, orange, green, yellow and all.

Image: My mom in 1972, a young mother and a student of Law, a smoker till this day

The 1980s arrived with a bang! Our Marshal on a white horse, Tito, died. That event in Yugoslavia was perceived by everyone as an apocalypse. From the child sitting at its desk at school, looking through teary eyes at the picture of Tito on the classroom wall, to the ninety-year-old man in his house, listening to the news on an old radio, pouring himself a rakija (a 50 proof drink made from grapes) in a small glass, and then spilling some on the floor – for the soul of the dead, possibly even crying “dear Tito!” Our saviour, who brought all the different nations together into one Yugoslavia, built bridges with Asia, Africa, Europe, and the USA. He met with all the important leaders of his time. He was a celebrity, and he was visited by numerous celebrities. Yugoslavia was a real player on the world map. At the time, his funeral was the largest state funeral in history.

But that year, 1980, was also a personal catastrophe for my mom. My parents divorced and she was alone in an adopted city. But all the friends and family that were dear to her now abandoned her since they all had been my father’s friends and family. She was left alone with two children, an uncertain future, and an unstable job in a city that suddenly became strange and distant. And then the legal struggles and hatred between the once young lovers began. She won in court. The legal system was still functioning. The mother had a right to her children, no matter if the father had many connections and was a big-shot doctor. But he wouldn’t accept defeat.

My mom was living with me and my sister in a rented basement, again as in the times of socialist confiscation. But now the tyrant wasn’t the state that the people loved, but the man she once loved, and who wanted to take back his son. She had to go to work and there was no one to keep her children safe. Many times my father would just come around and take me from the street or from school. My mom was a stranger in a strange land and the only way to get me back was with the help of the police. That was my life back then, being kidnapped by my father. Then the police would come banging on the door, my grandparents telling me to hide, followed by a forceful entry, police pulling me out of my hideout, and bringing me back to my mom. But why just me, why not my sister?

My paternal grandfather was a Montenegrin highlander, a soldier who came to Bosnia to fight with the partisans and who took part in two of the most decisive battles of WWII, those at Neretva and Sutjeska. What does that have to do with anything? Well, in Montenegro, when a little boy hops on a bus, if an elderly woman is sitting down, she must stand up for the boy to take her place. You would imagine that the right thing to do is the opposite. But no, not in Montenegro, because a boy is an heir to the family name, meaning a woman is important solely as the potential bearer of a little boy. That’s why my sister was left alone, while I was kidnapped over and over and over again. My mom decided that it was enough. She was doing enough psychological damage to her family. She packed her stuff and took us to the railway station. Then my father, a well-informed person, as it seems, showed up again and took me by force. I cannot imagine what went through my mom’s head in the moments before she got on that train to Skopje with my sister and left me with my father. But I can only imagine that, with her maternal instinct, she knew that if she stayed the situation would only get worse. She was in a foreign city with no one to protect her and her children. This way, her boy was with his father, who was capable of doing anything just to have him. It must have meant that he loved him dearly and wouldn’t let him suffer.

* * *

I was three years old and left with my father, grandfather, and grandmother. I was told to call my grandmother “Mom,” which I did, but deep down, I knew that wasn’t right. The ghost of my real mom that I couldn’t picture anymore always seemed to float around me. Sometimes it was a smell, a feeling of warmth, or a sound and I knew it was her, sending me messages from wherever she was. But I had no cognitive recollection of her even later, in 1984, when my grandfather called her “a gypsy-woman”. Firstly, “gypsy” was a pejorative word in Yugoslavia, meaning someone without a home, a wanderer, and a poor person. But my mom wasn’t poor. She was from the southern part of Yugoslavia that had—and still has—a large Roma population that is considered a part of the community. So, by doing that, my grandfather insulted two nations with one strike, Roma and Macedonian, but also my mom and me. He was a socialist warrior, and she was the daughter of an industrialist. Should I add more?

After that, she came to Sarajevo many times and asked to see me, but my father wouldn’t let her. Instead, he filled my head with fears that she was evil and was coming to get me and kidnap me. As the years progressed and I went to school there was always someone with me, my own personal bodyguard. Later on, when I was finally trusted to go to school on my own, I was always reminded of the possibility that someone was lurking behind me. Of course, my mom never tried to take me by force, but in my dreams an evil witch was chasing me, every night, ending with my falling into a bottomless well.

My mom never gave up on me. My paternal grandmother, who I loved, a woman with strict eyes and peach fuzz on her upper lip, ran the family as it became clear to me later. As soon as she died, my dad finally let me receive packages from my mom. Maybe he remembered what it was like to miss a mother and he felt sorry for me. Those packages were filled with the most interesting things for my school needs, some homemade cookies and sweets like those that I had never tasted before, and a letter from her and my sister, the two female figures, who I could only imagine what they looked like. I read the letter with awe and shame. Why shame? I was living in a manly world where the expression of emotions wasn’t allowed, and the letters were filled with emotions. They always ended with a plea for me to write something back, which I never did. My dad never forced me. Plus, I was a kid and just didn’t know what to write. If I could, I would, and I should have, as I learned later on in life. But as a kid – no way! – I was too afraid of emotions. They only meant one thing, that you were weak. And I didn’t want to be weak. My dad was also afraid, but he didn’t hide his angry emotions towards me. He expressed his anger in the form of ruthless beatings using his hands, his belt, his slippers, his foot… a really versatile means of expression. My granddad didn’t beat me but he had his own particular way of showing his anger, throwing things at me, like a cigarette lighter, his pipe, or a heavy glass ashtray. He was an avid smoker, what could I say. Anyway, beatings and throwing things at me were part of everyday home life, and luckily for me, I wasn’t at home for the most part of the day. Whenever I could, I escaped and visited my friends, played outside, hung out in the street, just like my mother’s ghost instructed me to do. I was a street rat, indeed.

Image: Me (“Tito’s pioneer”) with Vucko, the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics Mascot

It was then, like a bolt out of the blue, that my father decided to let my mom visit me. You know that strange feeling you get from meeting someone for the first time and knowing you remember them from somewhere? It was like that for me. Just weirder, I suppose, since her image and voice, her smell and feel was imprinted in a part of my brain that I couldn’t access consciously. She took me to the cinema, bought me ice cream, obeyed any and all my wishes. Never had anyone been so nice to me in my life. And as we stood in the hallway, before entering my house when our time together was up, she looked at me as if she never wanted to let me go. I felt awkward and insecure. What should I do? Should I go back and hug her? There had already been too many hugs for me in one day. Hell, no one had ever hugged me, ever! So I just said “bye” and went inside. I was in my toxic world again, and it felt like a relief. A man shouldn’t have emotions, right?

Break Rockin Beats of the 1990s

Several years passed and before I knew what was happening my father said to me: “Pack your things, you’re going to Kansas!” Well okay, it was Skopje, but it might as well have been Kansas or the Land of Oz since it was a whole new world for me. I got a new home, a sister and a mom, but lost a grandfather, father, and all my old friends. Was it a fair bargain? I don’t know. It was fair for my mom, for sure. She had both of her kids again, after ten years of battle. It was 1990 and the world entered into a new decade of Nirvana and grunge, MC Hammer and hip hop, break beats, and of course, a new catastrophe. This time my homeland was the target. Yugoslavia split in the most horrible and absurd way, by war. Sarajevo, my hometown, bore the brunt of it. It was under occupation for five years, and many of its inhabitants perished, while others fled to different parts of Europe or the world. Former professors, doctors, and lawyers were now cleaners, dishwashers, and garbage men. Life works in mysterious ways, right.

What did I do in this decade? Well, I was a teenager then. I studied a lot, listened to a lot of old and new music, learned the Macedonian language, exchanged my friends for my grandma’s large library of art and science books from the whole century, and spent some quality time with my mom and sister. It was indeed good when we weren’t afraid of the war that was banging on our doors. The 1990s for us were a mixture of good drum beats and bad rifle shots. My mom always kept a supply of non-perishable food, and energy sources like coal, oil, and wood as well as other things in the basement, needed in the case of emergency. She was always a single parent with a plan. Luckily, the war didn’t directly affect us in the nineties. But our neighbours, Serbia and Croatia, had a fair share of it. My homeland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, had it the worst. 100,000 people were killed, and more than two million displaced. But hey! – that’s the price of a senseless, brutal war that ended in 1995. It was time to change those Kalashnikov beats for the break beats of LTJ Bukem, Roni Size, Alex Reece, Goldie, Prodigy, and our own Kiril Dzajkovski. And damn, I liked those beats!

It was the end of the century, 1999, even the end of the millennium. I was a dishwasher in London, visiting my sister, and escaping another war in the Balkans, the Kosovo war, that could easily spill to my country of Macedonia as well. In the Asian restaurant where I worked, the main cook was a tall, happy-go-lucky guy, fond of drum’n’bass, and we bonded over musical stuff. The other cooks were an overweight black lady, a refugee from Africa, and a skinny guy from Wales. One evening, as we dined on rice with chicken legs and vegetables that the nice African cook prepared for us, the guy from Wales showed me some moves from the traditional dances of my country that he’d seen on TV. I was blown away! My mom came to London and stayed with me, but our visas were coming to an end, like the war in Kosovo. We went back to Skopje and life resumed in the old-fashioned transition-to-democracy kind of way. Living a prepper’s life. In the meantime people were simply hoping not to lose their job and become redundant workers in the workforce, like many.

Some people argued that the new millennium started in 2001, but it didn’t matter to us, since that year, yet another war began, and this time it was our lives on the line. We fled our country to Belgrade. I tried to continue my studies there but instead went to Montenegro to visit my father. Didn’t I mention what happened to him? Well, he had also fled his country of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992, and went to his father’s homeland, Montenegro, and started a new family there. So there I was, with his wife and three kids. Why the hell was I there? Well, let’s just say that one day I was planning to become a father myself and that I wanted to make my peace with him, just to be sure that I wouldn’t beat or leave my kids and become like him. That was the reason and I stayed true to myself. I made my peace with him and never saw him again. The Macedonian war ended on my birthday, August 13, and I went back home. My mom was happy to see me again, but there was some disappointment in her eyes. She never told me why, but I knew she was disappointed in me because I went to see my dad. I could explain that I did it for myself and for my future family, but I knew it wouldn’t matter. Maybe she was right.

Image: My mom in 2020

The new Millenium and the new reality of the 2020s

Soon I became a writer, some might say quite a fruitful and inventive one that inspired some young authors, in my own country at least. My mom watched me grow, become an artist, finish my education, get a job, a family, a house, “a f***ing big television, a washing machine, a car…” and all that Trainspotting jazz. It’s another story of survival; a shift from socialist to capitalist values, numerous casualties in the process, and my country, now renamed North Macedonia, trying to fit in with the big boys. The only problem is that Macedonia is a she, and like my mom, nothing comes easy to her. She has to struggle and to fight for every right that should belong to her. She is proud, and a bit older now, and her kids are grown up, wiser, and more independent. Her fate remains to be seen. This year, 2020, my mom celebrated her 70th birthday. New challenges have arisen, a life of fear and isolation, but this isn’t only our problem, a problem facing my country or my people. It’s the way of the world and a new story that awaits to be told by the unfolding of an uncertain future.

22.04.2020

Not even the winters are what they used to be

The snow in March 2020, two days after the onset of spring, was not good news. What about crops, and how long will our closed, poor, and small country survive on its own food supplies, how long will we last?

These questions tormented me as I remembered the visit my childhood friend Hare in February of this year. We haven’t seen each other for exactly thirty years, since that 1990 when I left Sarajevo, my skateboard in the trunk of the red Lada Niva that my father had collided with years ago and then his neck was in plaster for a while. Sitting in the back seat of that car, on my way to Skopje, I saw the landscapes of my city that changed on the rear window like scenes from a movie. The girl that I liked on the playground playing tennis, the curved street and the big stairs we used to ride, the place where I fell and decided not to cry for the first time, Harris’s house on the corner between Leze Perera and Logavina Street, the former Cinema in the local “Local Community” where the shouts of Bruce Lee, the blows of Rocky and the shootings of Schwartzie from the movie Commandos still echoed.

The world of my childhood ends there and the world of adults begin. The screen becomes black. The cries of the people, the cries of the children, the shelling on the houses, the bullet holes on all the buildings, the mines hidden on the mountains to this day is a horror movie that I did not watch, but it is well known to my friends and their families who stayed there to guard their homes.

Some taxi driver now lives in my apartment, but did that apartment ever belong to me? My grandfather got it as a prominent fighter in World War II, a “medical phenomenon”, as Hare would say. Rambo and Commandos can’t even catch a glimpse of his thirteen bullet wounds, several taken out, most of them left in his body, so that I, in my childish wonder, could touch them and admire his stories from the war. Let’s play a game? Name a significant battle from Bosnia and Herzegovina from World War II – my grandfather was there!

Today, thirty years after I left that apartment and that city, Hare brought me a book. “Logavina, a street under siege,” about the experiences of an American journalist living in Sarajevo, the personal destinies of people who lived under occupation. “Our friend Beljo is also mentioned,” Hare told me. Yes, the Beljo, who constantly got into troubles and thus got the name (“belja” means trouble), a storky, blue-eyed and a boy that always was smiling who survived the war, the years of famine and occupation, burning books and all the furniture from home in the cold Sarajevo winters and then died on the first day of liberation. But I have told you that story, as well as all the other stories that have already been told. I don’t know if I will be able to read the book, although Hare read it, and my childhood friends, Grebo, the good, cheerful, and honest Grebo who survived the siege of Sarajevo, read the book.

Hare is my oldest friend. I know him since my birth, even he admits that I have given him the nickname that is still stuck with him. Today he is old, with a white beard and a bald head, but he has the same smile and joker eyes with which he made us laugh as children. Aren’t people’s eyes really the same all their lives? Except in old age, when they are obscured, it is as if they are putting a protective layer between themselves and the world because they have seen too much, they have survived everything, and everything is already clear to them.

We talked about the old days and how it snowed so much in Sarajevo in the winter that the snow surpassed our children’s heads. We left our homes and jumped straight into the snow. But you are also familiar with that story.

I commented that there have never been such snows in Skopje and that most winters are without it. “It’s the same in Sarajevo now,” he said, “global warming.”

Looking at the snow outside in front of my building, as it stayed on the trees and the empty playground without the usual children’s chatter, I think about why right now, when there is no one to cheer for it, the snow has decided to come back. In one of my stories I told that snow brings joy to children and anger to the elderly, now everyone is in the second category.

Hare was here and left. I didn’t tell him anything I wanted to tell him, and I waited thirty years to do so. I had a flashback again at the meeting with my father, in Herceg Novi, Montenegro, in 2001, while there was a war at home in Macedonia. I wanted to meet him and to get him out of the system, to tell him that I would not be a father like him, that I would not leave and forget my children. And I really didn’t do that. But in the act of caring too much for my children, I made them unprepared for life. I understand that now. The rest of us who have been mistreated or left alone have learned to fight and to succeed. Did my father inadvertently do me a favour? That thought bothers me and disturbs me. The feeling that all you have done out of goodwill turned out bad. But, as I often say, “Whatever you do as a parent, you will make a mistake.” I hope I have also done something good!?

I left Hare in front of his hotel in the centre of my city, Skopje. “Thank you for letting me talk,” he told me, and I replied “Eg … wh … zr …” and that was it. The last thing I said at our first meeting in thirty years. Thousands of thoughts in Macedonian and Serbo-Croatian competed in my head, and none of them made sense. “You live here now,” my mother’s words from thirty years ago when I moved to Skopje were repeated. Indeed, my thoughts are not speaking in my mother tongue, for a long time.

Could I have done something different, say, tell something I didn’t say in my books? Would there be a difference? What would have changed? Whether the writer lives to write or writes to live is an eternal dilemma that I still cannot unravel.

It’s time to get back to reality. I’ve been here for a long time, I’m not what I used to be, that kid is left somewhere there, on the corner between Lese Perera and Logavina, laughing inside Hare’s home and watching TV with him, playing with the turtle in his yard, running out and gathering friends, and then all together running to our playground with a ball in hand and so on all day! Let him stay there.

We are here and we are watching the snow that brings us worries instead of joy. Childhood is over.

23.03.2020

Language:

Pages

Recent Posts

NYT > Books > Book Review

NYT > Books > Book Review

- Book Review: ‘El Niño,’ by Pam Muñoz Ryan April 18, 2025Pam Muñoz Ryan’s “El Niño” combines magical realism, climate fiction and coming-of-age sports tales.

- Book Review: ‘The Gate, the Girl and the Dragon,’ by Grace Lin April 11, 2025A mythical lion cub stuck in the modern world must harness the power of stories to save his family and return home.

- New Books About Cartoons That Will Bring You Back to Childhood April 4, 2025Mine came flooding back as I read Raina Telgemeier and Scott McCloud’s “The Cartoonists Club” and Jerry Craft and Kwame Alexander’s “J vs. K.”