3 Minutes and 53 Seconds – list of songs

Here is a list of songs mentioned in Bert Stein’s book 3 Minutes and 53 Seconds.

Playlist: 1980s / 1990s / (1980s во 1990s) / 2000s or separately:

1980s Hello

Michael Jackson – Thriller (1984)

USA for Africa – We are the World (1985)

Survivor – Eye of the Tiger, from the movie “Rocky IV” (1985)

Europe – The Final Countdown (1986)

U2 – Where The Streets Have No Name (1987)

Simple Minds – Don’t You Forget About Me (1985)

Guns N’ Roses – Welcome To The Jungle (1987)

Iron Maiden – Seventh Son of a Seventh Son (1988)

Bobby Mcferrin – Don’t Worry, Be Happy (1988)

Tajci – Hajde Da Ludujemo (1990)

1990s

Toto Cutugno – Insieme: 1992 (1990)

Larry Wright – from the movie “Green Card” (1990)

Vanilla Ice – Ice Ice Baby (1990)

R.E.M. – Losing My Religion (1991)

Spermbirds – My God Rides a Skateboard (1986)

Spermbirds – Americans are cool (1986

Bad Religion – Big Bang (1989)

Snuff – I Think We’re Alone Now (1990))

Red Hot Chili Peppers – Give It Away (1991)

Rage Against The Machine – Killing In The Name (1991)

Bad Religion – Recipe for Hate (1993)

Whitney Houston – I Will Always Love You (1992)

Primus – My Name Is Mud (1993)

Disciplina Kičme – Buka u modi (1991)

Ace of Base – All That She Wants (1993)

Cypress Hill – Insane In The Brain (1993)

Body Count – Body Count (1992)

Last Expedition – Keljav Dabar (1994)

The Prodigy – Out Of Space (1992)

The Prodigy – Their Law (1994)

Massive Attack – Protection (1994)

Tricky – Hell Is Round the Corner (1995)

Beastie Boys – Fight For Your Right To Party (1986)

Beastie Boys – Sabotage (1994)

Sepultura – Roots Bloody Roots (1996)

Sepultura – Ratamahatta (1996)

Robert Miles – Children (1996)

Goldie – Timeless: Inner City Life, Pressure & Jah (1995)

Dead Can Dance – Nierika (1996)

The Chemical Brothers – Block Rockin’ Beats (1997)

Alessio Bertallot – B Side on Radio Deejay (1997)

Apollo 440 – Ain’t Talkin’ ‘Bout Dub on Radio Deejay (1997)

Daft Punk – Around The World (1997)

Rabih Abou-Khalil – Arabian Waltz (1996)

Hungarian Gypsy’s violin (1998)

Korn – Freak on a Leash (1998)

Faith No More – We Care a Lot (1985)

Marilyn Manson – The Dope Show (1998)

Jamiroquai – Deeper Underground (1998)

Lauryn Hill – Everything Is Everything (1998)

E-Z Rollers – Walk this Land (1999)

Red Hot Chili Peppers Californication (1999)

Red Hot Chili Peppers – Road Trippin’ (1999)

2000s

Moloko – The Time Is Now (2000)

Gorillaz – Clint Eastwood (2001)

System Of A Down – Chop Suey! (2001)

Radiohead – Pyramid Song (2001)

Depeche Mode – Dream On (2001)

Daft Punk – Harder, Better, Faster, Stronger (2001)

Darkwood Dub – Život počinje u 30oj (2002)

Red Hot Chili Peppers – By The Way (2002)

The Streets – It’s Too Late (2002)

Tricky – Evolution Revolution Love (2001)

The White Stripes – The Hardest Button To Button (2003)

The White Stripes – Seven Nation Army (2003)

Foo Fighters – Times Like These (2003)

Franz Ferdinand – Take Me Out (2003)

The Black Eyed Peas – Let’s Get It Started (2003)

Wim Hof or D-r Kneipp – it doesn’t matter. Just breathe in, and let yourself go – into the cold!

Wim Hof Method is taking over the world! You have probably heard the famous quote “Breathe in, letting go!” or “The cold is my teacher” by Wim Hof, but who is Sebastian Kneipp and in what way are those two connected? Let me tell you from my personal experience.

Wim Hof – right on!

Wim Hof is a Dutch weirdo and practitioner of extreme endurance records in the cold. I became familiar with him after his visit to Joe Rogan Experience, a podcast that I started following as early as 2010. I was mesmerised by Wim Hof’s persona, his eccentricity, but even more by the simplicity and effectiveness of his method. Of course, I tried the breathing part and it felt great, but I didn’t try the cold showers, and forgot the most important part – commitment.

I dabbled in the method from time to time, before going to swimming in the cold pool and when I felt down, but it wasn’t until several years ago when I got sick that I realised its potential. One night I was shivering and my fever was rising like crazy. My brain filled with images and sounds from the past and it felt like when I was child and hallucinating from the violent fevers. Then something told me to sit up and start breathing. I was breathing not only with my lungs but also with my mind in determination to win over this thing that was winning over my body. I breathed deep and deeper until I almost passed away. I remembered that as a kid I was trying to hold my breath for a long period of time, but only succeeded to go to 1 minute and 15 seconds at most. In the last session of many I looked to the clock and saw 3 minutes 30 seconds. I didn’t have time to wonder at my new record, but at the feeling of happiness, my fever was completely gone and I didn’t even feel sick anymore. I became a Wim Hof believer, because “doing is believing”, like he says.

Several moons passed as I dabbled in the Wim Hof method, but didn’t try the cold showers, I thought that breathing was enough, and I wasn’t disciplined. It was the isolation and the global fear of the invisible enemy that brought me back to the method. This time I did it right, breathing, cold showers, meditation and exercises. My results kept rising, and I felt great, no depression in isolation, motivating others and fulfilling my time to the fullest. Of course, there’s still much to learn and to achieve for me personally, but I am truly grateful to Wim Hof and his findings.

Where does the method come from and how I came familiar with it

Then I begin thinking about the roots of the method. I remembered the sight of the kids, even kindergartens, in Russia outside in their bathing suits, rubbing snow on their bare skin, to improve immunity. The Russians and other nations that live in cold environments are also known for their baths in the frozen lakes.

The positive effect of the cold and cold water is known to early civilisations. Ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman civilizations practised it, in Ancient Greece it was called the Water Cure and Romans bathed in frigidariums. Cold shower therapy is also used in ancient indian Ayurvedic medicine and classic yoga practices that recommend cold morning showers.In the modern world and in the US athletes heal their inflammation from excess exercise by extreme cold using cold baths and cryotherapy. In the past in Europe the popularity of so-called Hydrotherapy was spread by Sebastian Kneipp and his book My Water Cure (1886) that was reprinted more than fifty times and in many languages.

Being from south of Europe (although that’s a whole nother story where my country fits in the european context), I remember it was 1997 and I was away at the time, a student at the University of Bologna in the small Italian city of Cesena and I have missed some of the important happenings in my country of Macedonia and its neighbouring countries. Such were the serbian protests against Milosevic and the end of an nationalistic era. Youth of my country was inspired by the serbian example, but only from the point of massive protests or throwing eggs at the government buildings. The serbian protest were anti-nationalistic, and our were large student and high school nationalistic protests of macedonians against faculty lectures in albanian language. Then many people lost their life savings in banks as a result of pyramid schemes that cost some of them even their lives. And lastly several people were killed and many injured because they lifted a flag of Albania in Macedonia. It was a boiling point and many people expected that after the war in Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Serbia, we were the next and the last war-appointed place in the long string of ex-yugoslavian wars.

In those circumstances my sister was graduating from the Academy of Fine Arts in Skopje with her installation/exhibition entitled Walking on Cold Water According to Dr. Kneipp, installed within the Institute of Physical Rehabilitation in Skopje. But why Dr. Kneipp and why there?

It was several years ago that I spent my whole summer in the Institute of Physical Rehabilitation healing my arm that was broken, operated upon, merged with a metal plate and fourteen screws, and in the process they screwed up the nerve that was controlling movements of the fingers. Besides that, my elbow was an immovable joint from being too long in the casket. So, being fourteen years old, the medical personnel thought I would heal in no time – except for me it was eternity, whole summer spent in hospitals, instead with my friends or preparing for the highschool exam, I spent my time learning how to write with the other arm.

In the meantime I visited the Rehabilitation centre where first they attached electric current to my arm and stimulated the nerve and the muscles. It was painful and uncomfortable. I clenched my teeth and looked the other way. In the small room there was the hospital bed I was on, electrical appliances for torturing patients, a table and two chairs. On one chair there was the nurse, and on the other a mother with a baby. The two women talked, and the baby was crying. It was obviously paralized, born that way, as I got to know from the mother, and it wasn’t getting better. But, she had hope and was doing anything she could. The nurse took the electrodes from my arm and I left the room without a word, ashamed of myself and with a great sense of guilt that I had been feeling sorry for myself.

The next room looked like a kindergarten, and indeed there were many figurines and 3D geometric shapes, that you were supposed to play with, in an orderly and preprogrammed way just to stimulate your nerves. There was a girl there that I liked. She was around my age, she looked me back, but both of us immediately looked the other way. She was doing the same exercises, and I looked at her hand. Her fingers were small and underdeveloped, like fingers of a baby on a child’s hand. She noticed my look and her gaze changed immediately.

I got out of that room feeling even more depressed. Then they sent me to the “paraffin room” and I wondered what was all that about. In the waiting room there were no more babies and kids, but old and wrinkly people that looked at me like I didn’t belong there. I was called and entered a room with a big aluminum pot. A nurse was mixing the contents of the pot with a long wooden paddle. What the hell was that all about, I wondered. Was she going to boil me and eat me like the children in the Hansel and Gretel story? No wonder there weren’t other children outside that room! Well, soon enough she pulled a big, soaking wet and boiling hot towel and wrapped it around my hand. It hurt like hell! I wanted to scream and swear at the nurse, but then the image of the paralized child appeared before my eyes. I decided to keep my mouth shut and wait for my arm to boil or whatnot. Then they unwrapped the cooked meat and put my elbow under an infrared light and that was it.

The last room looked like a physical education hall. “Do they expect me to jump some hoops or whatever?” I thought to myself. A nurse came and sat me in a chair, put a whole lot of powder on my hand and started massaging my arm. Well, that wasn’t so bad. “What did you do to your arm?” she asked me. I was thinking of my options. The truth was unbelievable, but I was too lazy to invent something more believable like “I fell down the stairs.” I supposed that I’ll be spending a long time there so she’ll probably know the truth anyway.

“We were armwrestling and my arm broke,” I said. “Who was the other guy,” she asked in wonder. “A friend from school” I answered. “Well, listen” she stopped massaging my hand and looked me straight in the eyes. “As soon as you resolve this arm thing, you go back to that friend of yours and you break his leg!” I laughed, but she seemed quite serious.

The lessons learned

I spent the whole summer in that place, and visited many other rooms. My sister sometimes came with me and wandered the long hallways. That’s how she got to know the place and discovered the rooms for the hydrotherapy according to the 18th-century Bavarian priest, Dr Kneipp. Later on, she discovered an 1926 croation translation of a medicinal book of alternative medicine called The Female Doctor in the House by Dr. Med. Jenny Springer. In the book there was a whole section on the practices of Dr Kneipp and the use of cold and hot water and its benefits. She included those pages in her exhibition that was held in the rehabilitation center and attracted a lot of people by the series of female nightgowns that were floating like ghosts in large, water-filled concrete basins; the white nightgowns were imprinted, in the area of the chest/heart, with drawings of Dr.Kneipp’s healing methods.

One day I was walking home and like it was nothing, my hand straightened itself all the way like it was something normal. After that the healing was easier and quicker. I got into highschool and didn’t break my friend’s leg. The nurse was apparently joking, but also told me another peculiar thing. “Make yourself an arm of plywood, tie your hand on it and sleep that way.” It apparently helped me since I didn’t wake up with a clenched fist and cramped up hand. The other nurse with the electrodes torture machine told me that I had to practice, not to leave the movement of the hand to the machine. Every time it lifts my hand I have to move it also. Even if my hand doesn’t move, I was supposed to move it in my mind. And so I did. In the beginning, the movement was only in my mind and then like a miracle it materialised itself into reality and my hand moved. Oh, what happiness the small thing in life could bring to us!

Several years later, in 1997 when I finished highschool and my sister had her exhibition I didn’t think much about the rehabilitation center or Dr. Kneipp. But as I started practicing the Wim Hof Method I realised it drew much inspiration from the practices of the Bavarian priest and older cultures that practised the deep breathing pranayamas, the yoga asanas and especially the cold bath.

It indeed has a lot of benefits, especially when you combine the cold water and the hot sauna, the cold opens the peripheral capillaries and brings the heat to the organs, and the hot opens them up and circulates the heat and the blood back to the surface. It may seem like an old practice that bases its findings on the antique and middle age humoral theory, but it’s benefits are more than visible in everyday life. When the cold hits the skin it’s like electricity that energizes your body. You’ll feel vital, energetic, happy and full of life!

Cold showers benefit not only your circulation and your emotional state, but also it strengthens your immune system and, contrary to the common beliefs, they keep you warm in the winter. It takes a lot of willpower to make yourself plunge into the cold shower, and just by doing that your self-belief and inner strength rises. The antidepressant effects on the mood, the autonomic nervous system and the endocrine system in combination with the deep breathing are already well and scientifically proven. You can check the facts and the scientific studies online.

Wim Hof, Dr. Kneipp, whatever it takes, but try to be balanced

Wim Hof gets quite a lot of attention, especially today, but we shouldn’t forget the age old practices, and personalities like dr. Kneipp. Life and health is not an isolated thing, although we are forced to live in isolation today. Dr. Kneipp proposed hydrotherapy as a means of bettering one’s health, but also in combination with other methods like using botanical medicines, exercise, nutrition and balance. All of these things could be practised at home, and are useful tools in these times. Maybe the most difficult is the last aspect of balance. Indeed, whenever I personally felt doubt or wasn’t trying enough for whatever reason, my Wim Hof Method results were declining. We shouldn’t forget the age old saying that in a healthy mind lies a healthy body and that the mind is the first thing we should take care of before plunging ourselves into the cold. Or maybe the cold could reset the mind and help the body? Well, like Wim Hof says “doing is believing”, so don’t believe, just do it!

25.04.2020

“Isolation” is not just a song by Joy Division

On the “modern” experience of feeling isolated and imprisoned through the eyes of a citizen of an isolated country

Surrendered to self preservation,

From others who care for themselves.

From the song “Isolation” by Joy Division (1980)

I’ve been living in an isolated country for three decades now and the feeling of helplessness that surrounds today’s world is very familiar to me and my compatriots, indeed. Since the last decade of the 20th century, the world has enjoyed the emergence of grunge and drum and bass, alt rock, broken beats and dubstep, among other musical genres. Ex-Yugoslavia survived some different beats and breakups, several wars, political and economical instability, embargos and blockades from outside, changes of names and identities, transition of governments, massive unemployment and “brain drains” and a fair share of personal turmoil. My country of today’s North Macedonia lived all of it and more, and we as its citizens felt as prisoners, small, insignificant, fearful, deprived, isolated and powerless to change our state of being. Seems familiar?

School as a prison

I fled the city of Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) in 1990 when the rain was still made of water instead of led and settled in the peaceful southern city of Skopje in Macedonia. Both cities were still a part of one state of Yugoslavia, and just a year later we were separate states on a course to nowhere. The former parts of Yugoslavia declared independence, and all hell broke loose. Former brothers turned against each other, families were separated, drinking rakija and traditional dances with holding each-other’s hands were exchanged for flying bullets and screams of agony.

In April 1992 my hometown of Sarajevo (Bosnia and Herzegovina) was under attack, and there wasn’t anything I could do about it. I didn’t know if my friends were alive or dead, later I found out that some of them left the country and had their fair share of the horrors of the fugitive life across Europe. The others remained, some of them fallen victims of the war, others its prisoners. They survived as they could, used books and furniture to heat their homes, or risked their lives when they got out to get food or water from the donations, there was shortage of oil, flour, gas, toilet paper… you name it. Seems familiar?

I was thinking often about them, but I couldn’t do anything to help them. When the warmongering beast awakens, there’s nothing anybody could do, really. In the meantime I had my own share of personal battles. I was in eighth grade in primary school and my best friend was attacked for being of a different nationality than the others. “What a load of bollocks!” any civilised person from the West would probably say, being right. But the mind of a person from the Balkans does not work that way. Here, a name or a surname, could cost you a life in those times, or maybe some broken teeth. While me and my best friend fled from the angry mob that wanted a piece of our dental insurance, we thought for ourselves: “We can flee today, but tomorrow we have to go to school again.” That’s the feeling of being trapped in your own skin, or environment, depending on the way you look at it, I suppose.

The prison is within our mind, but it can also be in our body

Well, let’s say that, in one way or another, my friend and I survived. Of course, it’s just another sad bullying story, we were the victims, all the others our tormentors, we cried, they cheered, we licked our wounds and life went on… Soon the school was coming to the sweet end in the form of the seemingly endless summer, and my friend and I were celebrating with our 50th arm-pushing contest. Maybe we were inspired by the 80s movie Over the Top of one of our childhood heroes Stallone, or maybe we were just boys, always competing, always measuring our strengths.

Let’s just say that I didn’t notice that in the meantime, counting from 1 to 50, my friend grew to be quite a large and strong young man, while I remained more-less the same. Just before realizing that, my arm snapped in half and I found myself in a hospital, confined to the surgical table, while the medical assistant was holding my nerve radialis, and the surgeon was bolting the two pieces of my humerus bone with a metal plate and fourteen screws. Yes, I woke up in the middle of the operation and was given another dose of anaesthesia, enough to kill a horse, or just to be sure that I wouldn’t wake up again, during the operation, of course.

The next thing I know is that my face was plastered from one to the other side of the table, but I couldn’t feel anything. I heard the voice of the medical nurse yelling “Wake up”, but the darkness, and numbness of my body was overwhelming and stronger than the reality, it almost felt more real and familiar. I was in a prison of my own body and it felt like forever. The voices were coming from the distant place of nothingness and timelessness, the same place where we all came from. And then the light, colours, feelings, smell of iodine and pain.

The prison of my body left, but soon after removing the seemingly another physical confinement, the cast, I realized that I couldn’t move my hand. The nerve was damaged during the operation, and my hand became the immovable object, heavier than a ton of bricks. Indeed, lifting a finger felt like that for a long time, the whole summer to be exact. While the others celebrated the end of a school year and the end of primary school education with the traditional tearing and throwing the books in the air I was confined to the rehabilitation medical centers with the elderly people who looked at me as someone to share their life stories and wisdoms to. I had no choice but to listen to them, it was my bad luck that I was raised to show respect to the elders.

Isn’t it that we only appreciate normal things in life when we don’t have them anymore? Well, when you lose your control over your dominant arm, and study to write with the opposite arm just to pass the highschool entrance exam, you look at things from a different perspective. Just as today – a simple walk in nature, a hug with a close friend, or a relaxed moment in a supermarket shopping for the family’s needs, seems like a distant and a long forgotten dream. When the things we take for granted are taken away from us, we begin to appreciate them and remember how it was like when we had them. The sad thing is that when we get them back we forget to be appreciative and go back to the old ways of wanting more, just as I forgot how happy I was to lift a finger and to be able to hold a pen. That’s our nature.

Homeland as a prison

A prison could be built of flesh or of beliefs, but your own country can be a big and impenetrable prison, also. And in the year of 1992 my country was closed from all sides, imprisoned in its own beliefs that she has a right to the name of the country of Alexander the Great. It was a pity that the world didn’t share our own beliefs.

As a token of our good will to be a part of the EU, the world and the progressive thinking we opposed the Yugoslav (Serbian) tendencies towards war. So we closed our borders towards our northern neighbour and the main export channel for our products. That devastated our economy since we have already been blocked on the south, towards Greece. Why? Let me tell you a little something about history – it’s a bitch, alright. Greece thought that we didn’t have any right to use the name Macedonia, although ancient Macedonia was also part of our territory, but ok. We were the b-side of the argument, small, weak and poor. The winners write the history, and we were destined to be losers.

What about the West and the East? Well, our version of the West is Albania, a country that was struggling itself, a former communist state. And they had it rough, allright. Our former socialist state of Yugoslavia was a theme park compared to Albania. We had all the personal freedoms, listened to western music and watched American movies. I mentioned Stallone, but he was only one of many of our childhood heroes like Schwarzenegger, Bruce Lee, Jackie Chan, Charles Bronson, Chuck Norris, Jean-Claude Van Damme and others. Our east neighbour Bulgaria was also a poor communist state, but their only interest in our country was if it was a part of theirs.

All of them, so-called eastern bloc countries, including Romania, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Hungary were considered as poor countries by the standard of Yugoslavia. If you exclude the political prisoners, the nationalization and appropriation of the personal belongings of the wealthy citizens, the average yugoslav bloke had free education and health care, functioning social support for the less fortunate and great housing policies for the workers. Yugoslavia was practically a free market socialist state and it’s GDP growth from 1950s to 1980s was often greater than most capitalist market economies of Western Europe and the US.

But since the 90s and the breakup of Yugoslavia, and the creation of the smaller national states, it has been a whole nother story. My country of Macedonia was particularly closed. Serbia and Croatia were at war, but they had friends, Russia and the EU or US. We, on the other hand, had no friends and no relations or a means to export or import goods from anywhere and in the middle of the process of transition from socialist to democratic government. It was an experience from hell. The once full markets were empty, no bread, milk, meat, flour. Since oil and the gas came from Greece, it never came, or if you waited for several days in the gas station, maybe you could fill a tank. It was a time when criminals ruled our sovereign country and smuggled cigarettes, coffee, sugar, oil, electronics, chemicals and even arms. All of those things were more worth than gold. Macedonian tobacco, famous in the world for more than a century, was given to the big players for literal pennies. They packaged it and sold it back to us via contraband for ten times fold.

Politicians or crime bosses had their bellies full and jiggling in laughter like a merry old Santa Claus. The ordinary people were desperate and hungry, their savings blocked by the state and the banks, left without a job or a choice in life, hungry, frightened and without perspective. In those circumstances my mother was sitting in the kitchen and talking to her friend, a medical person, about the processes of conserving food and water.

“If you open a bottle, the water is microbiologically clean for a week. Of course, tap water is full of chemicals and is safe for maybe a month if stored properly,” she was talking as if reciting a verse from a prepper’s book. My mother wrote all down and made a list: water, flour, oil, canned food… and kept a reserve of everything through the ‘90s.

Inflation was 450 percent, GDP was minus 7.5 percent, the unemployment rate was 30 percent and if you had the luck to be employed it was for a wage of $100. If by any chance you had foreign capital, banks took it from you. People were living like prisoners in their own country. Many people fled the prison, but not everyone had the chance.

A prison of the war

In those times of economic instability the fear of the shadow of the war approaching and covering our sunny southern state was always present. In 1991 ex-Yugoslavia separated and we gained independence, in 1992 the terrible war in Bosnia started, in 1999 it moved nearer, to Kosovo, and finally in 2001 it came to our country. It was a hell of a decade, and I was in the best years of my life, thirteen to twenty-three.

In the last year of the turbulent decade, or the first of the new millennium, Block Rockin Beats came to our country, and people started killing each other. Albanians wanted rights, Macedonians said, “maybe, but not with guns”, and as it happens in the Balkans, guns talked instead of words. The war already started in some other cities, but my city of Skopje was still safe. My mother was afraid that the military would take me to the front. I was a student of psychology then and didn’t believe that they needed anyone to talk to them about Freud, they needed warriors. But still, I was under stress that in any moment someone would knock on my door and take me away. When the bell rang we all jumped as shot from behind. One night I was awakened by explosions and rumblings and my heart nearly jumped out from my chest. As I was trying to locate myself in the darkness I realized that it was just thundering.

Soon after that, the thunder and rattles came to our city. There were real battles, not more than 10 miles from my house, helicopters, plains, mortar explosions, Kalashnikovs, and the sounds of war previously heard only in movies, were accompanying me in my study of Charcot, Helmholtz, Wundt, Piaget, Pavlov, Skinner and other pioneers of psychology. It was a real test of motivation and persistence of reason over emotion.

Being in your own country, in your own apartment, but still feeling like you are a prisoner of some big prison is very strange. If you didn’t hear the shootings for a brief morning when the sun bathed the trees and birds sang their spring song you stood in your window in wonder how nature doesn’t seem to care about our worries and just carries on. Maybe just for a moment, when the birds would fly in a flock, frightened by the sound of an explosion, you’ll maybe rejoice “We got you!”

Every spring, for ten years, we waited for that moment to come. We knew that someday we would be awakened not only by the sun, but also by the sounds of the war. And when it came, we were frightened like that flock of the birds on the tree in front of my house. But we couldn’t fly away to some other tree, instead we stayed in our city and in our homes and hoped that the war would end soon. It’s when the feeling of prison and isolation was in it’s peak. You trust no one and fear everyone. Even your best neighbor tomorrow could turn his back on you and shoot you. It has happened before, you know. When the war in Bosnia started the nearest neighbours that sometimes in their lives argued about something stupid, now had a licence to kill, and they used it. Everybody is a potential threat and if you want to live, you should be carefull. Trust no one, care for yourself. Does it seem familiar?

An epilogue – world as a prison

Well, the war ended in the summer of 2001 and it seemed like better times were coming. In the coming years there were several other instabilities and on-off shootings, but overall we were going in the right direction. Albanians got their deserved rights and we became a more democratic state.

In the following two decades we didn’t recover economically, and our neighbours didn’t support us. Hell, we didn’t even have a name for our state, since Macedonia wasn’t internationally recognised, or our people, language or religion. In the mind of the world we were an invented construct, non-existent entity and that sure had its toll on us. We struggled to be a part of the EU for decades and didn’t succeed, there was always an excuse that we didn’t fit with the big boys, although we did everything they asked from us.

Many people fled this big prison of a country, most of them fine, smart people. What was left of the was not the best. Some thugs, rough people that could survive and thrive in difficult situations. Let’s just say that I’m not one of those people and it’s quite difficult for me to be a fully developed human being in the circumstances where the higher intellectual needs are thought of as not important, even looked down on. The former schoolyard bullies that tormented my friend and me became rich and powerful and the country was imprisoned by such characters. Former proud communist party members that informed on their friends became free market and venture capitalist that ruled the unprotected majority.

In the year 2020 the three decades of our imprisonment ended, I was ready to accept that my adolescence and youth went in vain, but that my middle years would hopefully be better. My country got a new name – North Macedonia and the EU and the world was willing to recognize us as a part of it, even our most vicious enemy, our southern neighbor, that rejoiced in our struggle in the decades we were struggling. We were prepared for something big, for the greater future we dreamed of for three decades, to be able to travel and work abroad without waiting for visas, being humiliated from other states officials like we are lesser of a human beings, being able to work and earn something more in life. Many of our citizens felt it wasn’t right to change our name, but they were fed up of pure survival and wanted to live a full, happy and fulfilled life.

And just then, in the beginning of 2020, the world got isolated. It was as our bad luck passed on to the whole world. Now we were all living in fear, distrust, economic downfall and isolation, and there’s nowhere to run from the prison of reality. Does it seem familiar? Sure it does, now the whole world is like one big prison. But fear not, the human race is a tough customer, it survives, it adapts, just like nature, it’s a part of it. It will prevail, and build something better. It is a matter of time.

24.04.2020

No woman’s land – my mother’s homeland

A short personal account of Yugoslavia and Macedonia from 1920 to 2020

It was 1984 and I was a seven-year-old boy with long messy “Beatles-like” hair, as my doctor father used to tease, and a motherless “son-of-a-gypsy-woman” as my grandfather, a no-nonsense WWII veteran, used to say. Of course my hair was messy; I was being raised by two egomaniac father figures, neither of which told me to comb my hair or dress properly оr all the other things that a mother would normally say. My parents were separated by then, my mother, a descendant of bourgeois “traitors” and my father, a son of a proud socialist partisan warrior. I was living in the Marxist paradise and didn’t even know what my mom looked like, she was like a ghost figure, guarding me from a distance of a thousand miles, whispering in my ear not to worry, to leave my toxic home environment as much as I could and go outside to play with my friends. The street was a place of zen-like calm and eternal happiness. Indeed, it was a magical year – the 1984 Winter Olympics were being held in my city of Sarajevo, now just a collection of old shelled and bullet-riddled Austro-Hungarian buildings.

As I search through my memories like the pieces of a puzzle, I think to myself, “Damn, it could just as well have been Nineteen Eighty-Four!” People informed on others to the party, even their friends or relatives, who then often lost their jobs or, as my paternal grandfather, were taken to prison, although he was a socialist. In the meantime, my socialist country fell apart. We endured a hellish, pointless war. I lost all my childhood friends. But I gained a new transition-to-a-capitalist homeland. And, yes, a mother too. But let’s be fair. Living in Yugoslavia under socialism in 1984 wasn’t so bad. Later, some even called it “Coca-Cola socialism”. It was true that we had all the benefits of capitalism, even Coca Cola, although we preferred the domestic Cockta, which, to be honest, didn’t taste as good as the sweet dark American drink it aimed to replicate.

Throughout history, but also in any one particular moment of the Yugoslav past, there were many realities. In one of those realities, my mom was born in 1950. She was the granddaughter of an industrialist, who came from Czechoslovakia to Skopje in the 1920s with dreams of building his little capitalist kingdom. And he succeeded. Since then, Skopje has been part of the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes (1918-1929), the Kingdom of Yugoslavia (1929-1941), the Federal People’s Republic of Yugoslavia (1945-1963), the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia (1963-1991), the Republic of Macedonia (1992-2019) and the Republic of North Macedonia (2019). It’s mind-boggling, I know. In 1938 my great-grandfather, the Czech capitalist, built a factory called “Kumanovo” on the outskirts of Skopje, that had an automated flour mill, by my mother’s account the first of its kind in the Balkans. He also bought a lot of land, built several houses, and gave each of his daughters a house as a gift. Little did he and other wealthy people know that the war and, later on, socialism was coming.

Korda Family

My maternal grandmother, Nada Korda, was a large and strong woman, but only by her looks. In all of the pictures I have seen of her, she is gazing in the distance because she was burdened by a weak heart. Unlike her sisters, she didn’t want any material possessions. She had one wish only – to study art. Her father couldn’t say no to her and paid her tuition and living costs. Since there was no Faculty of Art in Skopje, she went to study in Belgrade, Serbia in 1938. When she finished her studies in 1942, she came back to Skopje. And like everyone else, she survived by tenacity and sheer will to live. In 1944 she married a capitalist, a wealthy young man who rode motorbikes, greased his hair, and smoked expensive cigarettes.

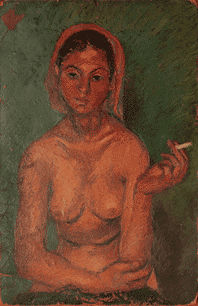

Image: Nada Korda (second on the left) with her relatives and one of her paintings above, Skopje, 1944

Image: “Gypsy Woman,” a painting by Nada Korda (1941)

Yugoslavia under the socialist regime was a wealthy country. There was no famine like in the USSR, and people were happy. Well, most of them, anyway. My paternal grandfather was imprisoned for five years in “Goli Otok” (literally “Naked Island” since there were only rocks and no vegetation). It was a hell on earth for political prisoners and he sure wasn’t happy. He was, however, a socialist and a WWII partisan veteran with thirteen bullet holes to prove it. But that’s nothing compared to the “traitor capitalist bastards” of my maternal grandparents. All the factories and houses they built were taken away from them by the legal processes of colonization, nationalization, and expropriation. That was the reality of socialism, not only for the city folk but for affluent landholders with a lot of livestock. The official story was that the socialist state took all of their possessions for the wellbeing of the people of Yugoslavia. But the reality was that all the private belongings that the state commandeered went into wealthy private hands of the communist leaders, which made the people poor. Like one of my mom’s grandparents’ houses, that was given to a general who, simply, passing down the street, saw the house and liked it! The family was given one night to move out.

In those circumstances, all of my family from my grandma’s side left Yugoslavia and went back to Czechoslovakia. All but my grandma. She stayed in Skopje with her husband and they lived a happy life… Of course, there are no happy endings in real life, but hey, there’s no fun and joy in life without difficulties! Her dream of becoming a professional artist was crushed by the war, the socialist nationalization of wealth, her illness, and her family leaving her. But she had a husband and, more than anything, she wanted to be a mother. The doctors advised her against having a child since it would be too great a strain on her weak heart, but to no avail – it didn’t matter to her. So, in 1950, my mom was born. There are not many pictures of my grandma from that period, but in those that I mentioned before, she always seems distant and looking into the future, as if she could sense that she wouldn’t be around for very long to see her child grow up. When my mom was nine years old, my grandma died. She left behind a husband without the love of his life, a house full of books that she read while confined to her bed, and many unfinished paintings.

Sima Family

And what about my grandfather? Well, he was crushed, of course, but this wasn’t the first tragedy of his life. His father was a Vlach (Aromanian), a people believed to have introduced urban culture to the Balkans. By the end of the Ottoman Empire, my great-grandfather was mayor of Kochani in Macedonia, a city famous for its rice production. In the 1920s he came to Skopje, already a wealthy man. He bought a house in the famous Skopje neighbourhood of “Pajko Maalo”, and opened a fabric store called “Simic”. His original surname was a Vlach “Sima”, but in the times of the Yugoslav Kingdom it was changed to “Simic”. Later, under fascist Bulgaria, it became “Simov,” in Macedonia “Simoski,” and finally back to Sima. That’s one of the wonders of the Balkans, changing your identity is quite a regular thing.

Image: Jika Sima, 1935

He and his wife had five children, two boys and three girls. The two boys went to university and graduated in economics, one in Paris and one in Skopje. After the death of their father, they ran the family business. The older one married a Bosnian woman and they moved with their two young children to Bosnia at the beginning of WWII. On the day of their arrival, the father and the little daughter, called Biljana, were killed in a Fascist ambush and died on the bus. The mother and the son survived and came back to Skopje. The grieving wealthy family gave the house in “Pajko Maalo” to the wife of their brother, and my grandfather called his first and only child – my mother – Biljana, in memory of the young seven-year-old daughter of his older brother.

Image: The girl that was killed in WWII (1940) and my mom who was named after her (1958)

As Socialism knocked on the doors of my family’s fortune, the “Simic” fabric store and all the possessions they had were taken. My mom lived with her family in rented flats and houses. But my grandfather, Jika Sima, didn’t give up. He opened a sporting goods store in Skopje called “Sport,” and then a furniture store called “Jugoexport”. He was part of the administration of the country’s best soccer club, “Vardar”, and was active in promoting winter sports, founding the “Mountaineering Union of Macedonia”. He was a tough capitalist nut to crack, but when my grandma died in 1959, he was devastated. Like all single fathers, he tried to fill the void of the maternal figure in the life of his daughter with strict rules, and he ruled his kingdom with a firm hand. Well, as you can imagine, that didn’t sit well with my mom. She was sent to live with her aunts in a village and had a seemingly pleasant rural experience filled with natural wonders before moving back to Skopje several years later.

My mother in socialist Yugoslavia

She was 13 years old when the new Socialist Republic of Macedonia, as a part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, lived through a catastrophe. Skopje was destroyed by an earthquake. Most of the buildings were destroyed. All the citizens of Skopje were given temporary living barracks. As the situation settled, my grandfather donated his barracks back to the state. He bought a house from his wife’s sister, where my mom still lives today. He was maybe the one and only person I know who gave back his barracks, since all the other citizens of Skopje built houses on top of their barracks, and later apartment buildings. And that’s how the city of Skopje came to be after the earthquake. It seems to me that my family has always valued hard work, sincerity, and effort. A lot was taken from them, but they never took anything that didn’t belong to them. My mom was raised by that principle, one I also believe in. Skopje was rebuilt with international aid from the East and West, and this brought to life some of the interesting brutalist architecture that Skopje was famous for in the 1960s and later on. In those times our socialist youth wasn’t any different from the youth of the capitalist countries. We also listened to British and American rock music and shook our hips to the sounds of The Beatles and The Rolling Stones.

The new decade was on the rise and my mom was 20 years old. Finally, let off the hook by her strict father, she enjoyed her time with her friends in Makarska, a city on the Yugoslav Adriatic Sea. It was then and there, at a party with the sound of Purple Haze by Jimi Hendrix in the background, that she met the man that would become my father. She left Skopje, and her father relocated all her belongings to Sarajevo. One year later she gave birth to her first love child, my sister. Sarajevo, the capital of Bosnia and Herzegovina, in the 1970s was a different city from Skopje. It was a real mixture of Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman influences, and a mixture of nationalities and religions as well. In socialism, everyone was equal regardless of their beliefs. And they really were – under Marshal “Tito” the people used to speak his name as if he was the one and sole deity. “Brotherhood and unity” was the slogan of the Yugoslav nation and all the people lived by it, especially in Bosnia. The Bosnian people had a real sense of humour too, and in those circumstances, my sister was born and six years later, I came along. It was the great old seventies, hard rock, sideburns, modern homes, electrical appliances, orange, green, yellow and all.

Image: My mom in 1972, a young mother and a student of Law, a smoker till this day

The 1980s arrived with a bang! Our Marshal on a white horse, Tito, died. That event in Yugoslavia was perceived by everyone as an apocalypse. From the child sitting at its desk at school, looking through teary eyes at the picture of Tito on the classroom wall, to the ninety-year-old man in his house, listening to the news on an old radio, pouring himself a rakija (a 50 proof drink made from grapes) in a small glass, and then spilling some on the floor – for the soul of the dead, possibly even crying “dear Tito!” Our saviour, who brought all the different nations together into one Yugoslavia, built bridges with Asia, Africa, Europe, and the USA. He met with all the important leaders of his time. He was a celebrity, and he was visited by numerous celebrities. Yugoslavia was a real player on the world map. At the time, his funeral was the largest state funeral in history.

But that year, 1980, was also a personal catastrophe for my mom. My parents divorced and she was alone in an adopted city. But all the friends and family that were dear to her now abandoned her since they all had been my father’s friends and family. She was left alone with two children, an uncertain future, and an unstable job in a city that suddenly became strange and distant. And then the legal struggles and hatred between the once young lovers began. She won in court. The legal system was still functioning. The mother had a right to her children, no matter if the father had many connections and was a big-shot doctor. But he wouldn’t accept defeat.

My mom was living with me and my sister in a rented basement, again as in the times of socialist confiscation. But now the tyrant wasn’t the state that the people loved, but the man she once loved, and who wanted to take back his son. She had to go to work and there was no one to keep her children safe. Many times my father would just come around and take me from the street or from school. My mom was a stranger in a strange land and the only way to get me back was with the help of the police. That was my life back then, being kidnapped by my father. Then the police would come banging on the door, my grandparents telling me to hide, followed by a forceful entry, police pulling me out of my hideout, and bringing me back to my mom. But why just me, why not my sister?

My paternal grandfather was a Montenegrin highlander, a soldier who came to Bosnia to fight with the partisans and who took part in two of the most decisive battles of WWII, those at Neretva and Sutjeska. What does that have to do with anything? Well, in Montenegro, when a little boy hops on a bus, if an elderly woman is sitting down, she must stand up for the boy to take her place. You would imagine that the right thing to do is the opposite. But no, not in Montenegro, because a boy is an heir to the family name, meaning a woman is important solely as the potential bearer of a little boy. That’s why my sister was left alone, while I was kidnapped over and over and over again. My mom decided that it was enough. She was doing enough psychological damage to her family. She packed her stuff and took us to the railway station. Then my father, a well-informed person, as it seems, showed up again and took me by force. I cannot imagine what went through my mom’s head in the moments before she got on that train to Skopje with my sister and left me with my father. But I can only imagine that, with her maternal instinct, she knew that if she stayed the situation would only get worse. She was in a foreign city with no one to protect her and her children. This way, her boy was with his father, who was capable of doing anything just to have him. It must have meant that he loved him dearly and wouldn’t let him suffer.

* * *

I was three years old and left with my father, grandfather, and grandmother. I was told to call my grandmother “Mom,” which I did, but deep down, I knew that wasn’t right. The ghost of my real mom that I couldn’t picture anymore always seemed to float around me. Sometimes it was a smell, a feeling of warmth, or a sound and I knew it was her, sending me messages from wherever she was. But I had no cognitive recollection of her even later, in 1984, when my grandfather called her “a gypsy-woman”. Firstly, “gypsy” was a pejorative word in Yugoslavia, meaning someone without a home, a wanderer, and a poor person. But my mom wasn’t poor. She was from the southern part of Yugoslavia that had—and still has—a large Roma population that is considered a part of the community. So, by doing that, my grandfather insulted two nations with one strike, Roma and Macedonian, but also my mom and me. He was a socialist warrior, and she was the daughter of an industrialist. Should I add more?

After that, she came to Sarajevo many times and asked to see me, but my father wouldn’t let her. Instead, he filled my head with fears that she was evil and was coming to get me and kidnap me. As the years progressed and I went to school there was always someone with me, my own personal bodyguard. Later on, when I was finally trusted to go to school on my own, I was always reminded of the possibility that someone was lurking behind me. Of course, my mom never tried to take me by force, but in my dreams an evil witch was chasing me, every night, ending with my falling into a bottomless well.

My mom never gave up on me. My paternal grandmother, who I loved, a woman with strict eyes and peach fuzz on her upper lip, ran the family as it became clear to me later. As soon as she died, my dad finally let me receive packages from my mom. Maybe he remembered what it was like to miss a mother and he felt sorry for me. Those packages were filled with the most interesting things for my school needs, some homemade cookies and sweets like those that I had never tasted before, and a letter from her and my sister, the two female figures, who I could only imagine what they looked like. I read the letter with awe and shame. Why shame? I was living in a manly world where the expression of emotions wasn’t allowed, and the letters were filled with emotions. They always ended with a plea for me to write something back, which I never did. My dad never forced me. Plus, I was a kid and just didn’t know what to write. If I could, I would, and I should have, as I learned later on in life. But as a kid – no way! – I was too afraid of emotions. They only meant one thing, that you were weak. And I didn’t want to be weak. My dad was also afraid, but he didn’t hide his angry emotions towards me. He expressed his anger in the form of ruthless beatings using his hands, his belt, his slippers, his foot… a really versatile means of expression. My granddad didn’t beat me but he had his own particular way of showing his anger, throwing things at me, like a cigarette lighter, his pipe, or a heavy glass ashtray. He was an avid smoker, what could I say. Anyway, beatings and throwing things at me were part of everyday home life, and luckily for me, I wasn’t at home for the most part of the day. Whenever I could, I escaped and visited my friends, played outside, hung out in the street, just like my mother’s ghost instructed me to do. I was a street rat, indeed.

Image: Me (“Tito’s pioneer”) with Vucko, the 1984 Sarajevo Winter Olympics Mascot

It was then, like a bolt out of the blue, that my father decided to let my mom visit me. You know that strange feeling you get from meeting someone for the first time and knowing you remember them from somewhere? It was like that for me. Just weirder, I suppose, since her image and voice, her smell and feel was imprinted in a part of my brain that I couldn’t access consciously. She took me to the cinema, bought me ice cream, obeyed any and all my wishes. Never had anyone been so nice to me in my life. And as we stood in the hallway, before entering my house when our time together was up, she looked at me as if she never wanted to let me go. I felt awkward and insecure. What should I do? Should I go back and hug her? There had already been too many hugs for me in one day. Hell, no one had ever hugged me, ever! So I just said “bye” and went inside. I was in my toxic world again, and it felt like a relief. A man shouldn’t have emotions, right?

Break Rockin Beats of the 1990s

Several years passed and before I knew what was happening my father said to me: “Pack your things, you’re going to Kansas!” Well okay, it was Skopje, but it might as well have been Kansas or the Land of Oz since it was a whole new world for me. I got a new home, a sister and a mom, but lost a grandfather, father, and all my old friends. Was it a fair bargain? I don’t know. It was fair for my mom, for sure. She had both of her kids again, after ten years of battle. It was 1990 and the world entered into a new decade of Nirvana and grunge, MC Hammer and hip hop, break beats, and of course, a new catastrophe. This time my homeland was the target. Yugoslavia split in the most horrible and absurd way, by war. Sarajevo, my hometown, bore the brunt of it. It was under occupation for five years, and many of its inhabitants perished, while others fled to different parts of Europe or the world. Former professors, doctors, and lawyers were now cleaners, dishwashers, and garbage men. Life works in mysterious ways, right.

What did I do in this decade? Well, I was a teenager then. I studied a lot, listened to a lot of old and new music, learned the Macedonian language, exchanged my friends for my grandma’s large library of art and science books from the whole century, and spent some quality time with my mom and sister. It was indeed good when we weren’t afraid of the war that was banging on our doors. The 1990s for us were a mixture of good drum beats and bad rifle shots. My mom always kept a supply of non-perishable food, and energy sources like coal, oil, and wood as well as other things in the basement, needed in the case of emergency. She was always a single parent with a plan. Luckily, the war didn’t directly affect us in the nineties. But our neighbours, Serbia and Croatia, had a fair share of it. My homeland, Bosnia and Herzegovina, had it the worst. 100,000 people were killed, and more than two million displaced. But hey! – that’s the price of a senseless, brutal war that ended in 1995. It was time to change those Kalashnikov beats for the break beats of LTJ Bukem, Roni Size, Alex Reece, Goldie, Prodigy, and our own Kiril Dzajkovski. And damn, I liked those beats!

It was the end of the century, 1999, even the end of the millennium. I was a dishwasher in London, visiting my sister, and escaping another war in the Balkans, the Kosovo war, that could easily spill to my country of Macedonia as well. In the Asian restaurant where I worked, the main cook was a tall, happy-go-lucky guy, fond of drum’n’bass, and we bonded over musical stuff. The other cooks were an overweight black lady, a refugee from Africa, and a skinny guy from Wales. One evening, as we dined on rice with chicken legs and vegetables that the nice African cook prepared for us, the guy from Wales showed me some moves from the traditional dances of my country that he’d seen on TV. I was blown away! My mom came to London and stayed with me, but our visas were coming to an end, like the war in Kosovo. We went back to Skopje and life resumed in the old-fashioned transition-to-democracy kind of way. Living a prepper’s life. In the meantime people were simply hoping not to lose their job and become redundant workers in the workforce, like many.

Some people argued that the new millennium started in 2001, but it didn’t matter to us, since that year, yet another war began, and this time it was our lives on the line. We fled our country to Belgrade. I tried to continue my studies there but instead went to Montenegro to visit my father. Didn’t I mention what happened to him? Well, he had also fled his country of Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1992, and went to his father’s homeland, Montenegro, and started a new family there. So there I was, with his wife and three kids. Why the hell was I there? Well, let’s just say that one day I was planning to become a father myself and that I wanted to make my peace with him, just to be sure that I wouldn’t beat or leave my kids and become like him. That was the reason and I stayed true to myself. I made my peace with him and never saw him again. The Macedonian war ended on my birthday, August 13, and I went back home. My mom was happy to see me again, but there was some disappointment in her eyes. She never told me why, but I knew she was disappointed in me because I went to see my dad. I could explain that I did it for myself and for my future family, but I knew it wouldn’t matter. Maybe she was right.

Image: My mom in 2020

The new Millenium and the new reality of the 2020s

Soon I became a writer, some might say quite a fruitful and inventive one that inspired some young authors, in my own country at least. My mom watched me grow, become an artist, finish my education, get a job, a family, a house, “a f***ing big television, a washing machine, a car…” and all that Trainspotting jazz. It’s another story of survival; a shift from socialist to capitalist values, numerous casualties in the process, and my country, now renamed North Macedonia, trying to fit in with the big boys. The only problem is that Macedonia is a she, and like my mom, nothing comes easy to her. She has to struggle and to fight for every right that should belong to her. She is proud, and a bit older now, and her kids are grown up, wiser, and more independent. Her fate remains to be seen. This year, 2020, my mom celebrated her 70th birthday. New challenges have arisen, a life of fear and isolation, but this isn’t only our problem, a problem facing my country or my people. It’s the way of the world and a new story that awaits to be told by the unfolding of an uncertain future.

22.04.2020

Not even the winters are what they used to be

The snow in March 2020, two days after the onset of spring, was not good news. What about crops, and how long will our closed, poor, and small country survive on its own food supplies, how long will we last?

These questions tormented me as I remembered the visit my childhood friend Hare in February of this year. We haven’t seen each other for exactly thirty years, since that 1990 when I left Sarajevo, my skateboard in the trunk of the red Lada Niva that my father had collided with years ago and then his neck was in plaster for a while. Sitting in the back seat of that car, on my way to Skopje, I saw the landscapes of my city that changed on the rear window like scenes from a movie. The girl that I liked on the playground playing tennis, the curved street and the big stairs we used to ride, the place where I fell and decided not to cry for the first time, Harris’s house on the corner between Leze Perera and Logavina Street, the former Cinema in the local “Local Community” where the shouts of Bruce Lee, the blows of Rocky and the shootings of Schwartzie from the movie Commandos still echoed.

The world of my childhood ends there and the world of adults begin. The screen becomes black. The cries of the people, the cries of the children, the shelling on the houses, the bullet holes on all the buildings, the mines hidden on the mountains to this day is a horror movie that I did not watch, but it is well known to my friends and their families who stayed there to guard their homes.

Some taxi driver now lives in my apartment, but did that apartment ever belong to me? My grandfather got it as a prominent fighter in World War II, a “medical phenomenon”, as Hare would say. Rambo and Commandos can’t even catch a glimpse of his thirteen bullet wounds, several taken out, most of them left in his body, so that I, in my childish wonder, could touch them and admire his stories from the war. Let’s play a game? Name a significant battle from Bosnia and Herzegovina from World War II – my grandfather was there!

Today, thirty years after I left that apartment and that city, Hare brought me a book. “Logavina, a street under siege,” about the experiences of an American journalist living in Sarajevo, the personal destinies of people who lived under occupation. “Our friend Beljo is also mentioned,” Hare told me. Yes, the Beljo, who constantly got into troubles and thus got the name (“belja” means trouble), a storky, blue-eyed and a boy that always was smiling who survived the war, the years of famine and occupation, burning books and all the furniture from home in the cold Sarajevo winters and then died on the first day of liberation. But I have told you that story, as well as all the other stories that have already been told. I don’t know if I will be able to read the book, although Hare read it, and my childhood friends, Grebo, the good, cheerful, and honest Grebo who survived the siege of Sarajevo, read the book.

Hare is my oldest friend. I know him since my birth, even he admits that I have given him the nickname that is still stuck with him. Today he is old, with a white beard and a bald head, but he has the same smile and joker eyes with which he made us laugh as children. Aren’t people’s eyes really the same all their lives? Except in old age, when they are obscured, it is as if they are putting a protective layer between themselves and the world because they have seen too much, they have survived everything, and everything is already clear to them.

We talked about the old days and how it snowed so much in Sarajevo in the winter that the snow surpassed our children’s heads. We left our homes and jumped straight into the snow. But you are also familiar with that story.

I commented that there have never been such snows in Skopje and that most winters are without it. “It’s the same in Sarajevo now,” he said, “global warming.”

Looking at the snow outside in front of my building, as it stayed on the trees and the empty playground without the usual children’s chatter, I think about why right now, when there is no one to cheer for it, the snow has decided to come back. In one of my stories I told that snow brings joy to children and anger to the elderly, now everyone is in the second category.

Hare was here and left. I didn’t tell him anything I wanted to tell him, and I waited thirty years to do so. I had a flashback again at the meeting with my father, in Herceg Novi, Montenegro, in 2001, while there was a war at home in Macedonia. I wanted to meet him and to get him out of the system, to tell him that I would not be a father like him, that I would not leave and forget my children. And I really didn’t do that. But in the act of caring too much for my children, I made them unprepared for life. I understand that now. The rest of us who have been mistreated or left alone have learned to fight and to succeed. Did my father inadvertently do me a favour? That thought bothers me and disturbs me. The feeling that all you have done out of goodwill turned out bad. But, as I often say, “Whatever you do as a parent, you will make a mistake.” I hope I have also done something good!?

I left Hare in front of his hotel in the centre of my city, Skopje. “Thank you for letting me talk,” he told me, and I replied “Eg … wh … zr …” and that was it. The last thing I said at our first meeting in thirty years. Thousands of thoughts in Macedonian and Serbo-Croatian competed in my head, and none of them made sense. “You live here now,” my mother’s words from thirty years ago when I moved to Skopje were repeated. Indeed, my thoughts are not speaking in my mother tongue, for a long time.

Could I have done something different, say, tell something I didn’t say in my books? Would there be a difference? What would have changed? Whether the writer lives to write or writes to live is an eternal dilemma that I still cannot unravel.

It’s time to get back to reality. I’ve been here for a long time, I’m not what I used to be, that kid is left somewhere there, on the corner between Lese Perera and Logavina, laughing inside Hare’s home and watching TV with him, playing with the turtle in his yard, running out and gathering friends, and then all together running to our playground with a ball in hand and so on all day! Let him stay there.

We are here and we are watching the snow that brings us worries instead of joy. Childhood is over.

23.03.2020

All the wars begin in spring

Vlado is the bravest man I know. No, Vlado is the smartest man I know. “Never let emotions overwhelm your logic,” he said in a Spock, from a planet Vulcan, manner.

It was March 2020 and the whole world was in a panic. Except for Vlado. Let me tell you a few words about him.

In 1996, I fell in love with a girl who was taking an Italian language course with me, and instead of telling her, I wrote her letters that I never gave her. What today’s Americans would call a classic “bitch move.”

That 1996 we were finishing high school, I was attending “Josip Broz – Tito” highschool, named after the former Marshal on a white horse, the pride of every Yugoslav, from a seven-year-old child who put Tito stickers all over the furniture in his home, to a seventy-seven-year-old man who kept a picture of Tito on his TV. Vlado was in his fourth year at the “Marija Sklodovska-Kiri” High School of Chemistry. One of these two characters will be remembered in history, you decide who.

Vlado was sitting on his couch in the small kitchen on the fifth floor of a socialist building in Skopje’s “Karposh” neighbourhood and listening to my stories about my unfulfilled love, that I have told him I don’t even know myself how many times. He did not comment on anything and occasionally responded with his standard “a-ha”. My place – the chair next to the small dining table, and above it a shelf with a radio cassette player and next to it cassettes of rock and hard rock bands from the seventies to the nineties of the last century.

The end of the last century was the time of cassette players, TVs with cathode-ray tubes, turntables, records, tape cassettes, video recorders and VHS cassettes, walkmen and CD players and other technology that is unnecessary today, but it seemed fantastic to us as futuristic as the Marty Mcfly’s hoverboard from the movie “Back to the Future”. Times have changed, but some things have not. Vlado’s eternal “a-ha” and his views on life and people.

The kitchen was no more than two meters wide to three meters long, but it was Vlado’s world. There I tried to unite my world with his and poured out my soul, while Vlado silently witnessed that cosmic act.

To the left of the kitchen – a magical space called “pantry” in which on a shelf were arranged all the necessary groceries for the family and of course the jars with domestic products characteristic of our environment – ajvar, pickles, lutenica… The barrel with the sauerkraut, of course, was stored in Vlado’s basement and his task was from time to time, especially when his mother decided to make sarma, to go there, to open it, to take one sauerkraut, to mix the “swamp” water as Vlado called it and to close the barrel properly. Vlado also had other household chores, such as vacuuming at home. All my friends and I had the same responsibility. In the Balkans and in that way the gender equality was maintained. The boys cleaned with a vacuum cleaner. Personally, I had other homework assignments, to scrape the bathtub, because “it’s a man’s job and requires strength”, and like all friends, I participated in family washing carpets (except Vlado who washed them himself and for a fee that seemed a cruel move from his parents, but eventually led to Vlado’s financial independence and success in later life), then painting the house and constantly moving furniture for different seasons.

Sometimes I washed the dishes not because I had to, but because I wanted to since the time I lived with my father and grandfather and I was often left alone at home. Then my greatest pleasure was to bring the chair to the sink, soak the sponge in water and detergent, and start rubbing. The foam that was collecting on my hands like sugar wool and disappeared with a jet of water seemed magical to me. Again alone and without choice, I sometimes fried eggs for myself, but then I realized that it was not enough to mix it, leave it in the pan and go to watch the cartoons. If you don’t want them to be “raw on the top, burned on the bottom”, you need to turn the egg while frying it, I learned early, maybe at the age of nine without the help of Jamie Oliver!

The smell of flour and home-made products went into my nostrils after Vlado opened the door of the pantry and took the bread out. He took out the board, cut a slice of bread and ate it like that – without anything. Such a simple and so practical act. No wasting time on opening jars and smearing unnecessary salty or sweat layers, just cut-out and eat!

As a continuation of “our” world was the terrace, no larger than a half-meter and maybe two meters wide, where in addition to the various wooden objects that Vlado’s father constantly cut and shaped with the knives he made and sharpened himself, there were standard building jardinieres with flowers, a small coffee table and two chairs. There we continued our conversation in which I forgot my fear of heights fueled by excursions through the narrow mountain roads across Bosnia and Montenegro where buses defy the laws of gravity.

In those extensions of our minds, we passed a part of our youths, my later unfulfilled loves and the only great love of Vlado that happened and disappeared without him sharing a word with me. That’s why Vlado is the bravest man I know.

In March 2020, the world was in a panic over what I called a “war with an invisible enemy.” Hidden at home and isolated from each other, as was the case in my hometown of Sarajevo, in a real war in the early 1990s, we lived in uncertainty. Vlado lived in the most affected country in Europe, Italy, and stoically endured everything that happened, with a rational approach and a cool head.

Then I remembered one of our conversations from the “time of the kitchen” in which we talked about his grandfather who came during the Second World War with the fascists in Macedonia, as a doctor, and fell in love with Vlado’s future grandmother, with whom he gave birth to several children. However, he never recovered from the war and, tormented by his own demons, returned to his home country, leaving his wife and children alone.

“I would go crazy in a war,” Vlado commented, identifying with his grandfather, and I saw it as a sign of weakness in him, someone I considered the most mentally stable person I knew. That conversation remained somewhere in the annals of the four walls between the kitchen table and the chair next to it, the couch and the cassette player, the bread-cutting board and the smell of flour. The life went on in a frantic paste that swallowed memories and experiences by the fear of the war and the uncertainty of our little country that always struggled to survive.

Returning to that conversation, after many years, in that terrible March 2020 (and all wars begin in the spring), I reminded Vlado of the conversation about his grandfather who did not remarry after the war, experienced deep old age and left all his property and money. of the church. However, he left to the descendants of Macedonia citizenship with which everyone left for his home country.

“You said you would go crazy in a war,” I said, “but what we’ve been going through this “kind of war”, and it seems to me that you would have endured the real thing quite well.”

“No, war is taking lives, and today it is about saving lives. Now it is most necessary to have a rational approach to things, “Vlado explained to me and continued:

“I am relatively calm because I have studied things in detail so that I can make an informed decision. I don’t want to be hypochondriac and live in fear all my life. Of course, one should be careful and responsible for one’s health. For immunity, take vitamins, keto diet, intermittent fasting, exercise, information from scientific sources, protection with masks and most importantly – not visiting the elderly people, we must protect them. My general preoccupation is not to infect others and that is why I am isolated, “Vlado concluded.

That is why Vlado is brave, but not like some “I will not be affected by this” people that live in our environment, and not only that – he is virtuous, because his preoccupation is with others, and then himself. That is why Vlado’s “madness” in the war would be not because of fear for himself, but because of the obligation to hurt others, I understood that in these times of war. It is a lesson that in difficult times we should all learn and repeat. I think that then the world would be a better place to live.

21.03.2020

About The Prodigy and music from our youth, traveling through time and other dimensions!

In December 1995, we were in the middle of the fourth year of highschool, and Skopje was filled with alternative youth, god almighty – it really seemed to be part of a parallel universe, because an incredible event from the other dimension – T-Festival happened!

Even before they were globally known, however, in the midst of popularity, The Prodigy came to our little forgotten city in the Balkans, which even the war avoided! But, of course, its shadow lurched over us, as we trembled daily under political insecurity, or under the pressure of an economic embargo from Greece, unemployment and technological surpluses were accumulating, we were shut down from all sides, a real powder keg in which one word, wrong gaze or act could have been a real “Firestarter”.

But then Firestarter did not exist yet, and “our” albums were for me “too much rave” album “Experience” and the favorite breakbeat “Music for the Jilted Generation”. I was headbanging my head on the song “Poison” because, as a metalhead, it was the only way I knew how to dance. Prodigy was somehow perfect for me, and “Voodoo People” was magical music for our “thrown-away” generation.

The Prodigy’s performance began and before I realized I found myself in the mosh-pit that turned me around and took me as a breathtaking river towards the whirlpool in which I sank. I got kicked in the mouth by Dr. Martens in all colors, and someone played a harmonica with his fist across my ribs, and finally someone threw me with a karate kick out of the whirlwind like a rag. As I regained consciousness, I realized that this was something different, I wasn’t at an ordinary mosh pit in Music Garden, this was a beast no one could control – and it was ready to swallow us!

We graduated from high school and the world was in front of us. We were young and filled with hope for a better future. I was getting ready to go to Italy for studies. Damn Informatics for the next millennium in la bella Italia. “You will find a job for sure, optics is the future,” my mother’s friend convinced me. What could go wrong? Well that’s another story.

We graduated from high school and the world was in front of us. We were young and filled with hope for a better future. I was getting ready to go to Italy for studies. Damn Informatics for the next millennium in la bella Italia. “You will find a job for sure, optics is the future,” my mother’s friend convinced me. What could go wrong? Well that’s another story.

We agreed with a friend of mine, Sandra, to celebrate our birthdays together and at the same time to say farewell to our friends. Everyone had to go their own way. She was born one day before me, on the 12th, me on August the 13th. Two years ago she appeared in our school as a powerhouse, she has lived in Africa, was educated who knows where in the world, she spoke better French than our professor, the methusaller Boshko who instead of teaching us “J’e sui” through tears in his eyes told us about the adventures of “pour Cosette” by Victor Hugo’s “Les Miserables”. Every class, from beginning to an end, to his end, God rest his soul.

We did the party at my home. The wall in the living room was a masterpiece made of my sister, with uneven gypsum and light from underneath which gave the look of a cave, and in the kitchen, crates of beer were emptied faster than I could refill them.

“It looks like in a caffe,” said Bojana, the indescribable love of my best friend from the highschool, and a friend from the bench, Vla. But the living room was empty at the expense of my room, where I had put all the unnecessary things from other premises, and right there against my will, my friends got together away from the music and the party. Boyana told Vla about her boyfriend, a dangerous biker and faculty student with whom an insecure high school student could not compete. Both of us were disappointed, I from the party, and he from the girl he was longing for. In fact, I had a similar diagnosis. Only my was in the Music Garden with her boyfriend and I had to see her right away!